Hello there. You are reading the TEETH newsletter, written and compiled by Jim Rossignol and Marsh Davies. This is a newsletter about table-top role-playing games: our own - that we’re publishing over here - and some by other lovely people whom we link below. Want us to see your work? Get in touch!

Our latest release is STRANGER & STRANGER, a 63-page, beautifully designed and illustrated campaign-length adventure based around the perilous tribulations of a gang of mutated villagers, an abomination, and a rather convincing stranger. Low prep and highly entertaining, it’s a taste of what to expect from our larger, forthcoming work. Please do check it out, and, if you are interested in supporting our exploits, please do buy a copy!

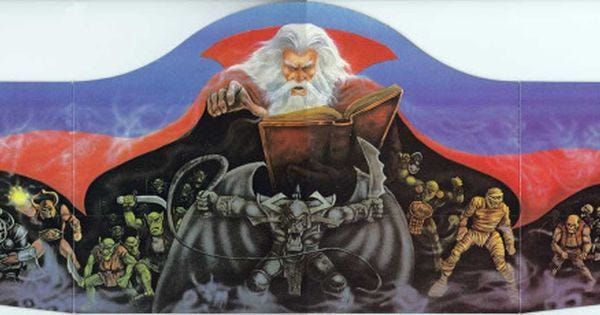

Anyway! This week, for reasons unclear, we played Heroquest on Tabletop Simulator. It should be said that since much of our group are dwelling well within their 40s, this was an act of lumpen nostalgia for most us, and yet for Olly, the spry, handsome youth of the group, it was a new experience. “It was fun dipping into you guy's childhood gaming memories,” he wryly quipped, making me run my fingers through the thinning hair on my head and sigh, “Having you play Zargon sort of preserved your group role as GM and ours as PCs, except we were all Stranger Things type kids playing this ‘80s game with oiled up barbarians and pointy eared elves. Quite a palate cleanser from the sombre tone we usually seek out, even if that tone inevitably turns comedic as dice roll!”

The comedic dice rolls were available to us in Heroquest, of course, but not always for the best of reasons. What was most striking about playing it again after several decades was how so many of the aspects of the boardgame dungeon-crawler were in place: the stat-driven baddies, the piles of cards, the multiple applications of dice types - it was all there. It’s very much a system, with a bunch of scenarios available, and the pseudo-GM referee allowing things to cater to human invention. Yet the implementation now seems utterly without finesse. Sure, it’s a game For Kids, but using 2d6 for random movement distances is straight out of the worst part of Cluedo. The designers did not forget to include the oldest fashioned boardgame tropes. (Which leads to a weird image of the barbarian dawdling one moment, zooming forward the next, untethered from need or intention.)

I played the evil wizard, because of course I did. Refering to oneself as Zargon in the third person is one of lifes distinct pleasures. And yet still I did not feel 14 again.

It’s better than Dungeon, though, which I also played recently, and is Not Good, despite what we remember.

Regardless, I feel like there’s going to be a few people who will regret their recent lavishly expensive Heroquest-reboots when they arrive…

Deeper & Down

All this had me thinking about the role of dungeons generally in our tabletop games, and why, why dungeons? A strange word to have dominate our hobby. Not one you want to say out loud in public all that much. Narratively, as Comrade Gillen likes to point out, there are key reference points to the root of our dungeon-theme: the labyrinth of Daedelus in Greek legend, containing the minotaur, and The Mines Of Moria in Lord Of The Rings, containing surely the grandfather of escalation-to-boss-encounter dungeon sequences. There are plenty of story reasons for dwarves and their friends to descend into a hole.

Yet it is not for lore that the dungeon exists in Dungeons & Dragons, but for gameplay: it is the core activity, with defined scope and constraints. A clear thing for players to engage in and a definite set of obstacles to overcome. Delve deeper, get more platinum coins. Other games were less focused, and arguable failed to gain the same traction.

Later, pondering this, and being an extremely lazy and derivative essay writer, I simply Googled the answer to Why Dungeons, and, like a student beginning his essay with the dictionary definition of the topic at hand, stumbled into this to-the-point formalisation from the gloriously-named CyberDefinitions.com.

DUNGEON means Closed-Off Area in an online gaming context. In RPG (Role Playing Games), a Dungeon is a hostile Closed-Off Area within which a player will encounter enemies. DUNGEONs are usually found in enclosed areas, such as castles, fortresses, or caves.

That’s the Cyber Definition. I love that unneccesary capitalisation. DUNGEONs.

But yes. The germ of the truth is obvious and apparent: dungeons are about keeping the characters under pressure. They should not be able to walk away from this situation, and the drama of dwindling hit points and emptying spell rosters is felt all the keener if they are a mile underground with just a Balrog-analogue between them and the Sword Of Iconicus. You cannot take your oil-slick barbarian off the board, he must open the next door.

Pressure, arguably, is one of those key vectors to understand how your game works, as nebulous as it might first appear. And I think that’s as true of narrative games as it is of those with a board and some orks: providing building peril works best if there’s no way to retreat and recoup, no time to tag out until the thing is done. A social dilemma is best dealt with if there’s no way to walk away from the people affected by it, just as you can’t retreat from the half-giant when the portcullis drops down.

Pressure need not come from being enclosed in a corridor with traps ahead and a gelatinous cube behind, either. Consider this much-shared quote from Blades In The Dark’s Jon Harper:

“The primary factor is pressure. The design of the setting forces the PCs into a pressure-cooker situation. The lightning barriers around Doskvol mean they can’t merely “leave town” if the heat gets too high. Killing isn’t the easy solution to problems that it is in other games (because of ghosts). Every valuable claim is already held by other factions, so making moves means making enemies, which is good for drama. The specific qualities of the setting are there to drive exciting play.”

The pressure here is social, factional, persona, and legal. It is not merely spatial, but situational in a wider web of forces. The dungeon is abstract: it’s the architecture not just of of the Lich King’s Crypt, but of the motivations which lock players into their aventure. In Blades the dungeon is as much the interlocking agendas of the various gangs and institutions as it is the fact that you can’t simply get out of Doskvol. And does that matter for the design of TEETH? Yes. Yes it really does. We absolutely want pressure to mount, even as you roam in a blasted landscape. The Vale might be wilderness, but it is cordoned, quarantined from traffic, with the players there only for a limited time. And, with corruption building as they do their monster-hunting work, will they be done in time to leave? Or will they find themselves trapped forever, like a Theseus whose twine got nibbled by plague rats. Getting that right is something we’re really excited about for the campaign length rules.

I should probably go and write those in more detail.

But first…

LINKS!

I completely missed the Merger crowdfund, and catching up on it now. A single-player Forged In The Dark game that’s “a mix of The Big Short and Cthulhu.” A game in which you struggle against corporations as actual flesh-and-blood entities, trading stress to get an edge in taking on “the corporate bodies”.

A Blades In The Dark character made in Hero Forge. I am very impressed!

The Carved In Stone Kickstarter intends to bring freely-available educational gaming to our understanding of the Pictish people. Did I link this before? I forget, either way, Comrade Gardiner reminded me to do so. 17 days left to pledge!

Business Card Dungeon Delve amused me largely because of the American Psycho reference. They really should sort out the formatting on the page, though, really made me uncomfortable, oh God.

Bubblegum Wizards. It’s fairly self-explanatory.

I had previously intended to link to GRIMDARK, which is an academic history of Warhammer, with just excellent cover art. Ideal christmas reading for a certain species of nerd, of course.

Oh and while we’re on the topic of Labyrinths, I appeared as a bit part character in this week’s New Yorker article profiling the world’s most prolific maze designer. So that’s a thing that happened.

Research this week was mostly about conspiracy theories and Holy Shit, people are nuts. (Via Gillen again. Awful man - sign up to his newsletter!)

—

Love you! x